Building a Future Where All Youth Thrive

Education is the most reliable pathway toward generational success. Here’s how Trinity's Racial Justice team is dismantling inequities for students of color in New York City.

At Trinity Church, when we think of a flourishing New York City, we think of young people first. Yet too many students of color don’t have access to the resources they need to succeed. The COVID-19 pandemic deepened existing racial disparities, with many Black and Latinx students slipping behind their peers in reading proficiency and graduation rates. As we reach the end of the year, a turning point looms: The $7 billion in federal pandemic aid that temporarily buoyed recovery will expire in 2026, raising the risk that more students in the nation’s largest school system will be left behind.

As a 328-year-old institution rooted in Lower Manhattan, Trinity Church takes seriously our responsibility to care for the youth of our city. Our commitment to students reaches back to 1787, when the African Free School was founded on Trinity land to provide education to Black youth. In the early 19th century, Trinity helped New York’s first Black Episcopal priest, the Rev. Peter Williams Jr., establish a school for young Black New Yorkers. During the mid-to-late 1900s, Trinity supported young people from marginalized communities through its summer camp program in West Cornwall, Connecticut, and by awarding grants to organizations in Harlem and the South Bronx working with youth of color.

Such efforts, of course, were small victories in a society that to this day remains mired in the legacy of slavery. Racial inequities in wealth, education, and housing continue to hold youth of color back from achieving their dreams — and Trinity is responding by broadening its commitment. Over the last six years, we have invested $18 million in projects intended to improve educational outcomes for students of color, through tutoring, mentoring, restorative justice, and youth leadership. Trinity also brings a dual perspective — as both a large-scale grant maker and an on-the-ground provider of youth programming — which uniquely positions us to drive change. We focus our work on dismantling systemic barriers tied to race, income, or ability, and envision a city where education is not the privilege of a few but a promise for all.

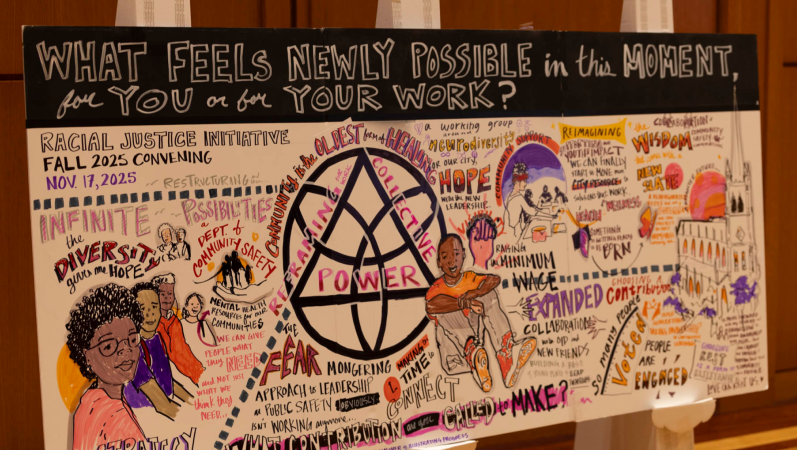

Trinity’s Racial Justice initiative reaffirmed this vision of New York City at its biannual convening at Trinity Commons on November 17. Gathering with 89 leaders representing 54 justice-oriented nonprofits, Tasha Tucker, the team’s managing director, outlined a five-year strategy that will expand and deepen Trinity’s work with youth.

“This is a defining moment. As public funding for youth programs grows more uncertain, Trinity remains committed to our young people,” Tucker said. “Over the next five years, we’ll walk alongside our grantee partners to make sure youth of color not only recover from the setbacks of the pandemic but rise as leaders, scholars, and change-makers in our city.”

The need for bold action becomes clear when we look at the data. More than 75 percent of the nearly 1 million students in New York City public schools are economically disadvantaged, and over 60 percent are Black or Latinx. Graduation rates for Black and Latinx students lag up to 14 percent behind their Asian and white peers. Only about 50 percent of Black and Latinx high schoolers are deemed “college-ready,” compared to nearly 75 percent of white students and 78 percent of Asian students.

When students of color face educational inequities, it can shift trajectories for their families across generations. Education remains one of the most powerful pathways toward long-term economic security. A Harvard study on social mobility found that access to quality education is one of the most important predictors of whether children surpass their parents’ income level. A college degree can be particularly transformative. Workers with a bachelor’s degree earn about 66 percent more than those with only a high school diploma, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

We’ll walk alongside our grantee partners to make sure youth of color not only recover from the setbacks of the pandemic but rise as leaders, scholars, and change-makers in our city.

Tasha Tucker, Managing Director, Racial Justice

Responding to the urgency of the moment, Trinity’s Racial Justice initiative hopes to chart a new way forward. Working with dozens of experts, grantees, funders, and public school leaders, the team examined grantees’ efforts to transform outcomes for youth of color, with an eye toward strengthening and scaling that work. Out of this collective vision emerged four pillars that now serve as foundations for the road ahead.

Literacy

The first pillar centers literacy as a key predictor of academic success. Research has shown that children who cannot read proficiently by third grade are far more likely to drop out of high school. Science-backed interventions, such as the model used by Trinity grantee Read Alliance, have proven remarkably effective in accelerating students’ educational trajectory. In fact, the nonprofit’s early elementary school participants advance a half year in reading skills after just one month of the program. By supporting early readers, Trinity aims to increase the number of Black and Latinx students reading at or above grade level.

Well-being

The second pillar emphasizes a positive school climate. Trinity will continue working with nonprofits such as Make the Road New York to replace punitive discipline in schools with restorative justice and social-emotional learning practices. The nonprofit has successfully campaigned for publicly funded restorative justice programming in schools and organizes Know Your Rights trainings for 1,000 youth every year.

Post-secondary success

The third pillar addresses inequities in college enrollment, retention, and graduation. Trinity grantees, such as the Urban Male Leadership Academy at the Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC), are giving students the skills and support needed to succeed. About 775 students receive mentorship, academic support, leadership training, and career exploration through the program every year, resulting in a graduation rate 30 percent higher than BMCC students outside the program.

Leadership development

The final pillar helps students improve their community, city, and society. It prioritizes youth organizing and activism as key strategies for improving academic performance, boosting emotional well-being, and developing future generations of social justice leaders. Through the work of grantees like The Urban Youth Collaborative, which trains youth organizers to promote positive school reforms, Trinity is encouraging the next generation to imagine a better future not only for themselves but also for their peers.

Over the next five years, Trinity’s Racial Justice team will partner with public schools and nonprofits to scale programs across its four pillars, with a particular focus on supporting populations too often overlooked — students of color with disabilities, in foster care, experiencing homelessness, learning English, or navigating school as over-aged learners.

Oluwatoyin Ayanfodun, founder of Tomorrow’s Leaders NYC, knows these challenges well. His nonprofit helps students who have been held back in school overcome social, emotional, and academic barriers. He has witnessed the breadth of obstacles confronting youth and the urgent need for a culture shift that allows students to see school not as an obligation, but as a place filled with possibility. That shift requires creativity and innovation — which is why Ayanfodun is greatly encouraged by Trinity’s efforts to prioritize youth.

“It’s a game changer,” Ayanfodun said about the Racial Justice initiative’s strategy. “I believe, with the work of the wonderful organizations funded by Trinity, we’re going to start seeing young people having much higher success rates in New York City’s public schools.”

The Rev. Phillip A. Jackson, Trinity’s rector, also framed the moment as an opportunity. “Especially in seasons of uncertainty and dislocation, we are called to reimagine what is possible. We must work together to build something better for the next generation,” he said. “We’re going to keep showing up for our young people because the future of this city belongs to them.”