10 Fast Facts About Trinity Church

After 328 years, Trinity has some stories to tell. Marissa Maggs, director of Trinity’s Archives, walks us through 10 of them.

Alexander Hamilton is buried in Trinity’s churchyard. But the jury’s out on whether he sat in the family pew on Sundays.

He’s the man on the ten-dollar bill, the architect of the American financial system, the main character of the hit musical by Lin-Manuel Miranda — and the most famous occupant of our churchyard. While Alexander Hamilton was making a name for himself in the history books, Trinity Church served as his primary spiritual home. Hamilton baptized many of his children here and offered his sharp legal mind to counsel the church in a few court cases.

We don’t have any records indicating whether Hamilton actually worshipped at Trinity, but his wife, Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, appears on an 1801 list of all the people who received communion at the parish.

George Washington was practically a regular (if only for a short time).

George Washington attended Trinity Church and St. Paul’s Chapel while the Continental Army was in New York during the Revolutionary War. When the war ended, our parish continued to offer spiritual support to Washington and other members of the newly formed American government. After Washington’s inauguration in Federal Hall as America’s first president on April 30, 1789, he and members of both houses of Congress walked six blocks north from Wall Street to attend a service at St. Paul’s Chapel. Washington regularly worshipped at St. Paul’s during the brief period when New York City was the capital of the United States.

It took three tries to build the Trinity Church you see today.

There have been three buildings on the land where Trinity Church currently stands. The first church, built in 1698, faced west toward the Hudson River. It burned down in 1776 during the Great Fire of New York. The second church opened in 1790. It faced Wall Street and was longer and wider than the first, with a steeple that soared to 200 feet. George Washington, then president of the United States, attended its consecration ceremony. But this church stood for only a few decades: In 1839, heavy snow caused the roof’s support beams to collapse. British-born architect Richard Upjohn was brought in to help with repairs and decided to completely rebuild instead. That work brought us the third Trinity Church, which opened in 1846 and still stands today. It’s considered one of the first and finest examples of neo-Gothic architecture in the country.

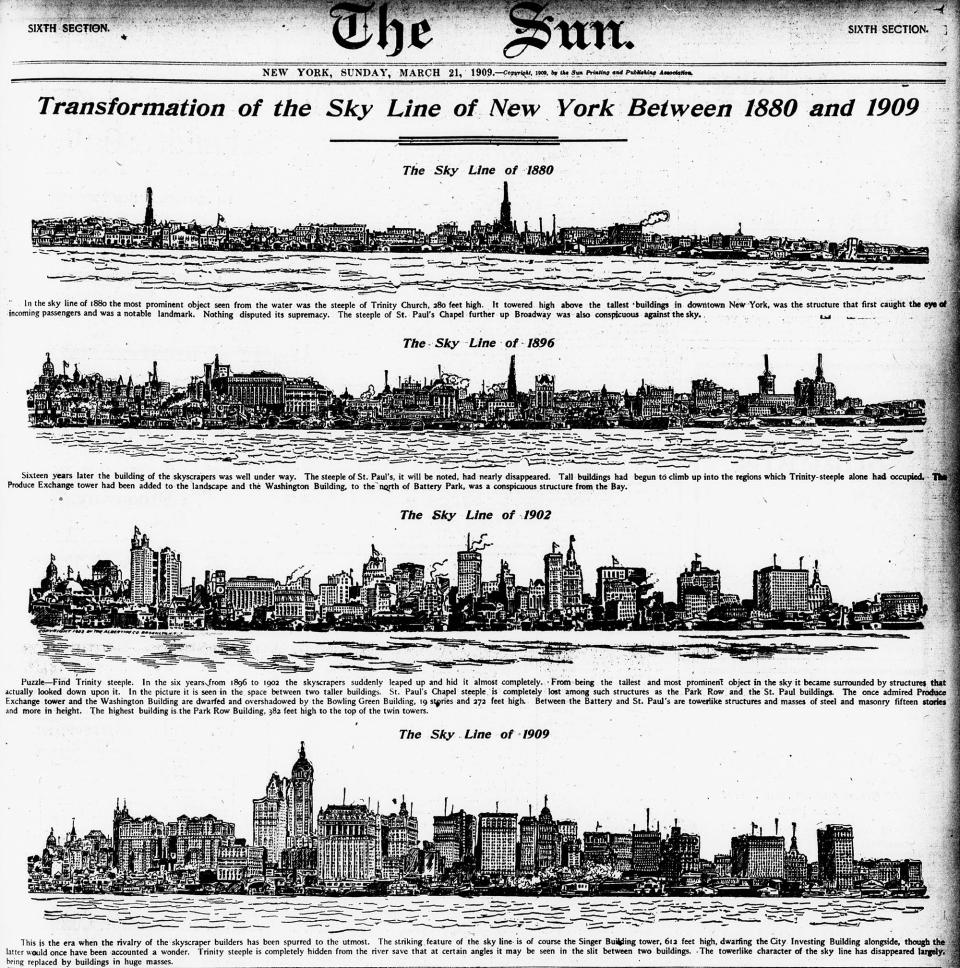

Trinity was once the tallest building in the United States.

With its 281-foot steeple, the third Trinity Church became the tallest building in the United States. It held that distinction for over two decades, until it was surpassed by St. Michael’s Church in Chicago in 1869. Trinity Church continued to tower over New York City’s skyline until 1890, when “The World Building,” the 309-foot home of the New York World newspaper, temporarily claimed the title of the city’s tallest building.

Forget Times Square — long before the ball drop, Trinity Church was where New York gathered to ring in the new year.

The belfry of the third Trinity Church featured a full octave of bells, capable of playing tunes — an NYC novelty in those days. Around the time the church was completed, New Yorkers began crowding into Lower Manhattan on New Year’s Eve to hear Trinity’s bell ringer, James E. Ayliffe, usher in the new year with hymns and popular songs. In 1876, The New York Times described how “thousands of men, women, and children representing all classes of New York society, from the poorest to the richest, stood quietly enjoying the glorious night and the ringing of the bells.”

The crowds grew noisier and more raucous over the years, with the Times reporting in 1885 that people “blocked the sidewalks … and struggled and pushed each other,” blowing cheap tin horns that drowned out the sound of Trinity’s bells. The noise grew so problematic that in 1893, Trinity’s rector, the Rev. Dr. Morgan Dix, cancelled the event. Under great pressure, Dix relented the next year and the custom of gathering at Trinity Church on New Year’s Eve continued. It eventually died out in the early 20th century, supplanted by the Times Square celebration.

Trinity has first dibs on whales and shipwrecks that wash up in New York Harbor.

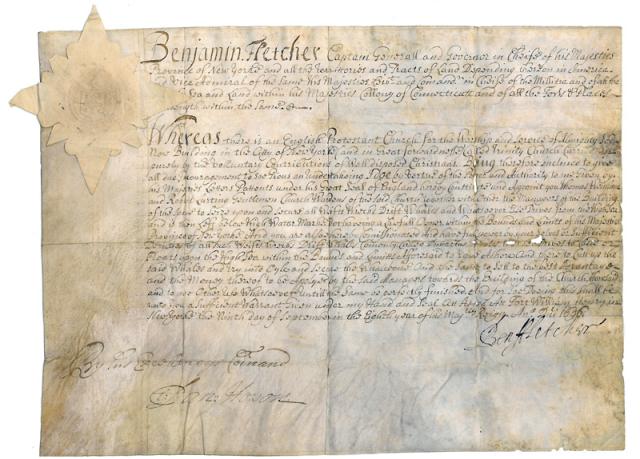

Like the leaders of any new church, Trinity’s early vestry members struggled to raise funds for their parish. In 1696, the colonial governor of New York, Benjamin Fletcher, granted a patent declaring that all shipwrecks and drift whales that washed ashore in New York Harbor would become the property of Trinity Church. Whales and shipwrecks were a considerable source of income at the time. Whales were used for a variety of valuable products, from lamp oil to corset stays. And shipwrecks would provide access to whatever goods were on the boats.

Trinity’s “Whales and Wrecks” patent is still technically valid. As far as we know, it’s never been enacted.

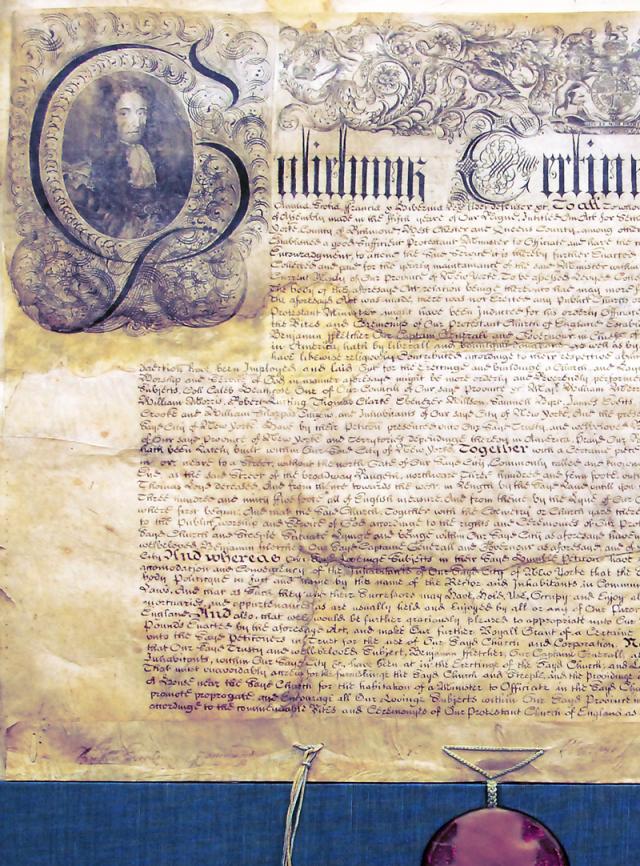

Our charter dates to 1697 — and we still have the original.

Before Trinity could become the first official Anglican church on the island of Manhattan, we needed permission from the crown to exist. King William III granted Trinity Church its charter in 1697, and we’ve kept it safe ever since. The original four-page document is preserved in a temperature-controlled vault in Trinity’s Archives. It was written in English — rare for the time, since most official documents were written in Latin or French. The charter came with an elaborate sketch of King William III and the king’s official red seal. The seal has degraded over the past three centuries, but the missing areas have been patched over with wax.

The charter serves as our incorporation document. It spells out, legally and spiritually, how we are to exist as a parish — establishing the rules of our vestry, the succession of rectors, and the bounds of the King’s Farm, a parcel of land along the western side of Manhattan that was leased (and later, permanently granted) by the crown to support Trinity’s mission and ministry.

The charter came with a tiny caveat — an annual rent of one peppercorn.

All the rights, properties, and privileges described in Trinity’s charter were granted to our church provided we pay King William III and any of his heirs or successors a yearly rent of one peppercorn. Imposing a fee was a way of binding a legal contract and was often not taken literally in those days (in fact, the term “peppercorn” was frequently used as a metaphor for a very small payment).

We don’t have any record of Trinity paying this annual tariff until 1976, when Queen Elizabeth II visited our parish and Rector Robert Parks presented her with 279 peppercorns in back rent. The queen accepted this symbolic gesture on the front steps of Trinity Church, where a plaque commemorates the event.

Trinity’s north churchyard was a burial ground long before our founding.

Our registers show about 12,000 burials in the north and south churchyards combined. Because of the Great Fire of New York, which destroyed the first Trinity Church building, our oldest burial register doesn't start until 1776.

Trinity’s north churchyard was used as a public burial ground as early as the 1660s, when it lay outside the city’s walls. The oldest legible gravestone in Trinity Church’s churchyard belongs to 5-year-old Richard Churcher, who died in 1681 — 16 years before Trinity officially became a congregation.

A real-life pirate helped build Trinity Church.

Captain William Kidd was a legendary 17th-century Scottish privateer turned pirate. He began his career as the successful captain of a private ship and was often tapped by the English government to defend their trade routes. He emigrated to New York in the 1680s, married a wealthy widow, and established himself as a respected member of society. When Trinity needed help constructing its first church building in 1698, Kidd stepped in. Trinity’s vestry meeting minutes from July 20, 1696, note that, “Capt. Kidd has lent a Runner & Tackle for the hoiseing [sic] up Stones as long as he stays here.” The runner and tackle created a pulley system that allowed workers to lift heavy stones during the church’s construction.

A few months later, Kidd and his crew set sail for the Indian Ocean to hunt for pirates. His reputation began to tank as reports surfaced that he was attacking ships without orders. He was ultimately hanged in 1701 for acts of piracy.

Although Kidd likely never attended services at Trinity, his name remained tied to the church. According to a 1718 pew list, Kidd’s heirs owned half of pew No. 4. (The other half was owned by the rector.) It’s possible that Kidd paid for several years in advance, which means his heirs remained pew owners 17 years after his death.

This article is based on earlier stories by Jim Melchiorre, Joseph Lapinski, and Marissa Maggs.