Black History is Trinity’s History

Reflecting on the strength and power of Black voices at Trinity Church

Black Americans’ courage, perseverance, and faith have shaped Trinity Church from its earliest days. Their stories stretch across the centuries: enslaved students who risked everything to attend Trinity’s night school, abolitionists whose faith compelled them to organize for freedom, Caribbean immigrants who found a spiritual home and infused our parish with new life. For 329 years, Black resilience has threaded itself through Trinity’s unfolding narrative, sustaining its spirit and strengthening its legacy.

In celebration of Black History Month, we’re revisiting a handful of these stories, tracing a lineage that continues to guide our parish today. This history — Trinity’s history — invites us to imagine what a more just, more faithful future might look like, and challenges us to continue the work of building communities where everyone can flourish.

The 1700s: A Hard Look at Our Beginnings

Reconstructing Trinity’s earliest Black history requires reading between the lines of records written by those who never intended to preserve Black voices. We can only find glimpses of what the Black experience was like at Trinity during the turn of the 18th century, hidden as asides within vestry minutes, contracts, and other archival records.

Here’s what we know: When Trinity’s first church rose in 1698, at least seven enslaved people dug its foundation and shaped its stonework. Their names were never written down in our archives, but their uncredited labor is the reason Trinity’s founders had a church to worship in. We cannot fathom the depth of their suffering, and we cannot forget their essential human dignity.

In the early 1700s, enslaved Black New Yorkers sought education and spiritual formation through the school founded by Elias Neau, a French Protestant who served on Trinity’s vestry from 1705 to 1713. Despite laws designed to restrict their movement and suppress their learning, Black students persisted. They met Neau in Trinity Church’s steeple for classes three nights a week, learning to read and write. They anchored themselves in the truth of God’s love for all people. Their determination defied the fears of Manhattan slaveholders who worried that Christian teaching would awaken a hunger for freedom. It did.

Trinity’s Vestry minutes tell us that by 1726, hundreds of Black New Yorkers had pursued baptism and communion. Their faith became a declaration of spiritual equality in a world that denied their personhood.

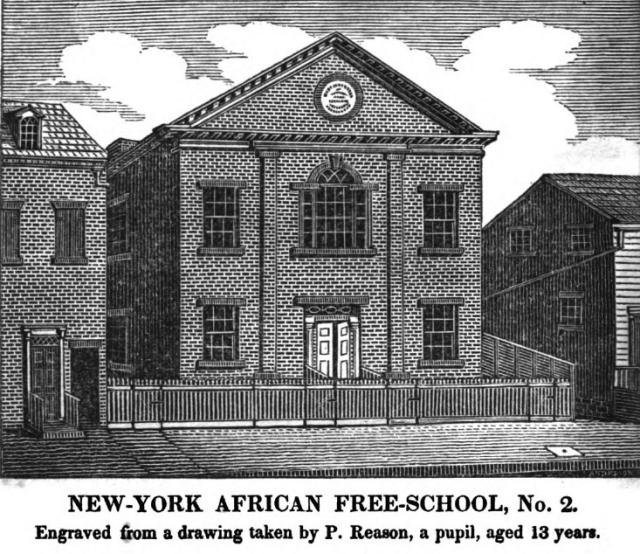

Later in the century, Black children continued to forge their own futures through the African Free School, which was founded on Trinity land in 1787. Within 30 years, the school was said to be teaching 100 pupils. Against extraordinary odds, these young scholars used every resource available to access an education and shape their own lives. They made a way out of no way — and carved a path for many who would follow.

The 1800s: A Leader Emerges

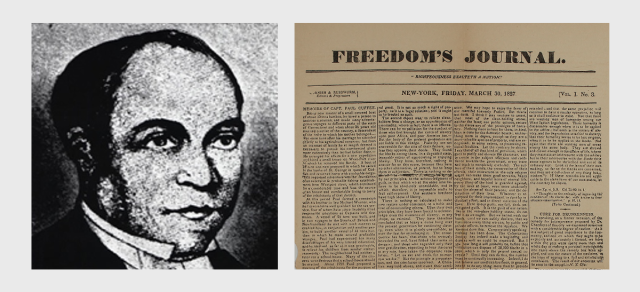

Among the African Free School’s most remarkable alumni was the Rev. Peter Williams Jr. The son of a Revolutionary War veteran, Williams was a gifted orator and visionary whose faith propelled him into public leadership. Barred from attending New York’s General Theological Seminary, which prepared Episcopal priests for ordination, Williams was privately tutored by the Rev. John Henry Hobart, then an assistant minister at Trinity Church and later the Episcopal Bishop of New York. Williams emerged as the voice of Black Episcopalians who, facing segregation at Trinity, petitioned the Diocese of New York for a church of their own.

In 1826, Williams became New York’s first Black Episcopal priest and the founding rector of St. Philip’s Church. Originally located in Lower Manhattan’s Five Points neighborhood, the church became an influential hub for Black activism, community development, and spiritual life.

Williams’ ministry extended far beyond the pulpit. He was a leading figure in the anti-slavery movement and helped launch Freedom’s Journal, the first Black-owned and operated newspaper in the United States. He organized mutual aid efforts for Black communities in New York. With Trinity’s financial support, he also started an Episcopal school for Black youth, ensuring the next generation had access to the education that had transformed his own life.

Williams used his voice to challenge injustice and uplift his community. He remained a respected leader in New York’s Black and abolitionist communities until his death in 1840.

The 1900s: Opening to the World

By the mid-20th century, Trinity’s congregation was beginning to reflect the changing face of New York City. Between the 1960s and 1980s, Anglicans from New York’s immigrant Caribbean communities began filling our pews, drawn by the liturgy and music they remembered from their homes. Their faith, service, and joy energized our church, and they paved the way for the diverse and vibrant community we have today.

Black youth also reshaped Trinity’s mission during this era. They found space for recreation, learning, and belonging in Trinity’s summer camp programs in rural Connecticut. By 1985, the vast majority of our campers were young Black New Yorkers. Trinity also deepened its engagement with communities in Harlem and the South Bronx during this period, awarding grants to organizations working with youth of color. Through tutoring programs, job training, arts and recreational spaces, and other community-run initiatives, Black youth drew strength from networks of support within their neighborhoods.

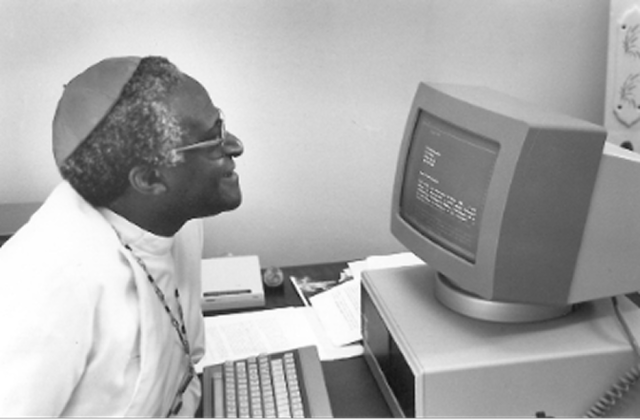

Internationally, Black leadership continued to inspire our global vision. Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s prophetic voice against apartheid resonated deeply within our parish. When censorship threatened his ability to communicate with South African clergy, Trinity supported the creation of a computer network that allowed his message to spread. The Archbishop preached at Trinity numerous times in the 1980s, bringing words of justice and liberation to our congregation. Through these visits and his ministry, Archbishop Tutu became a beacon of Christ’s love to our community, reminding us that faith must always stand with the oppressed.

The 2000s: The Future of Our Church

Today, Black youth continue to shape Trinity’s identity. At our Afterschool program, hundreds of teens from different races and backgrounds come to Trinity Commons to learn, lead, and build community. Scholars from the Trinity Voorhees Fellowship, which offers internships to students at America’s only Episcopal HBCU (Historically Black College and University), have enlivened our church with fresh vision, innovation, and leadership.

As public funding for youth programs grows more uncertain, we remain deeply inspired by the strength and brilliance of young Black New Yorkers. Last November, Trinity’s Racial Justice initiative outlined a five-year strategy that seeks to expand and deepen our commitment to youth of color. Through our grantee partners, Trinity is supporting youth across the city who are pursuing academic excellence, advocating for school reform, and becoming the next generation of justice-oriented leaders.

The Trinity Church we have today is the legacy of generations of faithful Black lives. As we look ahead, we give thanks for those who came before — and for the young people who are already showing us the path forward.