Five Things the Earliest Christians Knew About the Power of Inclusion

The first church communities discovered a truth that remains pivotal today: God’s expanding love invites everyone in.

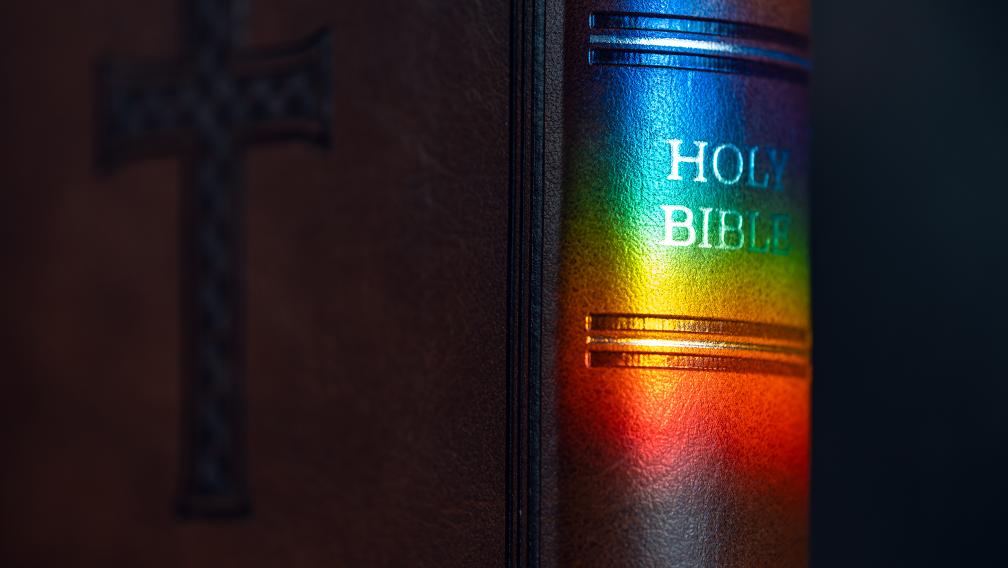

June is Pride Month in the United States. And on June 22, Trinity begins Discovery: Summer Sundays, a deep dive into the Book of Acts, the biblical story of Jesus’s followers in the years after his death and resurrection. You might assume the two have little to do with each other. How could Stonewall possibly relate to those early evangelists? Yet, if we take another look at the first-century Christian communities alongside the full scope of modern-day Pride, we can see more than a few similarities.

In both the early church, founded under occupation by the Roman Empire, and in LGBTQ+ communities facing difficult circumstances today, we see diverse coalitions of people coming together against the odds to work for a better world. Here are five lessons we can learn from the earliest Christians about what it means to love in a way that breaks down our divisions — and makes room for everyone.

Building inclusive communities that embrace difference

One of the first challenges the early church confronted was creating community across difference. Jesus was a devout Jew, and he called Jewish people to be his earliest disciples. Yet, beginning in the Gospels with folks like the faithful Roman centurion, a soldier who asked for Jesus’s help despite not being Jewish himself, and accelerating greatly after the miracle of Pentecost, described in the Book of Acts as the moment when the Holy Spirit empowered the disciples to speak many languages to preach the gospel broadly, Christianity took on many non-Jewish converts.

This created tension: Some, like the Apostle Peter, wanted to maintain their distinctive Jewish identity, while others, like the Apostle Paul, preached the full inclusion of everyone, regardless of their religious identity.

It’s no easy feat to hold shared and individual identity in tandem, especially in a world as complex, and divided, as ours.”

Chapter 15 in the Book of Acts tells how the church overcame these divisions. After witnessing undeniable evidence that the Holy Spirit had come to non-Jewish followers, too — Gentiles were joining the church whether or not they were wanted — the apostles gathered in Jerusalem to find compromise in light of God’s ever-expanding embrace. They agreed that Jewish Christians would keep their traditional practices, and Gentile Christians did not need to do the same.

While Paul could rightly say, in his letter to the early church in the province of Galatia, that in Christ there is “neither Jew nor Gentile,” distinctively Jewish Christian communities persisted for several centuries more.

Churches today face similar challenges. It’s no easy feat to hold shared and individual identity in tandem, especially in a world as complex, and divided, as ours. Yet the goal remains the same: to form inclusive communities without demanding that people abandon their God-given uniqueness.

Creating new relationships in chosen families

Life isn’t meant to be lived alone. Family, friends, and other types of kinship play an essential role in our flourishing. Moreover, it’s in these relationships that we learn to practice what Jesus teaches: love, justice, and compassion. However, as LGBTQ+ people in particular know, sometimes we have to create new, perhaps unconventional, families and communities.

While Pride Month offers a chance for queer folks and allies to celebrate the support of their families of origin, it’s also a time to be grateful for the chosen families who offer love, support, and solidarity, even when it’s not culturally expected of them.

Early Christians found in the church a similar alternative model for kinship. Jesus called his disciples his “mother and brothers and sisters.” Paul called his protégé Timothy his “son in the faith.” And the New Testament writings repeatedly emphasize adoption, or chosen relationships, as the central motif for God’s parental care for us.

Sometimes those relationships happily coincided with biological families, but the church also became family to those without that support. In chapter 4 of Acts, we learn that the earliest Christians shared all that they had with one another and distributed their possessions among them, so everyone had what they needed. That’s the type of care for one another that defies social norms.

Coming out, or telling the truth no matter the cost

Coming out, whether as Christian or queer, is risky business. We see this in Scripture: In John’s Gospel, when a man tells his community he’s been healed by Jesus — a scandalous truth that challenged their strongly held beliefs — even his own parents distance themselves from him. The author then notes that those who believed Jesus was the Messiah were being thrown out of their religious communities.

The coming out of LGBTQ+ people and Christians aren’t parallel: Queer people rarely feel their sexuality or gender is voluntary in the way religious commitment is; and Christianity claims people’s whole lives in a way queer identity does not. Yet both require the precarious vulnerability of self-disclosure.

Why then does anyone take the risk? Partly for the sake of the relationships described above. People want to be honest with themselves and others and build deeper, more meaningful connections in that authenticity. And many LGBTQ+ people experience something quite like what the apostles report in Acts: They simply cannot help but speak about the truths they have seen and heard.

Sometimes these truths are uncomfortable for those making assumptions about the way people should be, or inconvenient for the powerful benefiting from the status quo. Yet, for that reason, coming out can be a prophetic act that causes the kind of good trouble that disrupts unjust systems.

Remembering those who’ve come before

Sometimes the risk spills over into loss. Pride Month is a celebration but also a time to remember those who — whether due to violence, plague, or simply time’s march — did not live to see their work accomplished. Both those who protested in the streets and those who quietly built communities with space for difference contributed to the advancement of justice from which we all benefit. Their examples inspire us to continue their work in our own time, even when new obstacles or oppressions arise.

While Acts records the great joy that filled the early church, it’s quickly mingled with loss. Chapter 7 recounts the death of Stephen, the first Christian martyr who boldly spoke truth to power and paid the price for it. Most of the apostles ultimately shared a similar fate. But the Christian hope is that their efforts were “not in vain,” as Paul writes in his letter to the Corinthians. From death springs the promise of new, lasting life. As the early theologian Tertullian wrote, “the blood of the martyrs was the seed of the church.”

Far from an endorsement of holy war, Tertullian’s point was that the way early Christians answered violent oppression with nonviolence turned out to be the greatest testimony to Jesus’s message of radical, self-giving love, such that the church grew rather than shrank in the face of persecution. The fact that we celebrate Pride Month at all is likewise a testament to the labors of so many who have gone before.

Seeing God in everyone, even our enemies

Despite the progress of the last few decades, our country, and our churches, remain deeply divided over the dignity of LGBTQ+ people. In such times, it is easy to think that God is only to be found on “our side” and not with “them.” Yet the early church’s movement toward unbounded inclusion was only possible because of an openness to being astounded by where — and in whom — the Holy Spirit might be found.

This is a hard message for anyone to hear, because it requires accepting that the Holy Spirit might be at work among those with whom we disagree, even those whose behavior is prejudiced or oppressive. That is not to say God endorses unjust behavior, only that God moves in strange, wonderful, and sometimes imperceptible ways. God’s plans may be beyond what we can understand.

It’s because of that unfathomable power of the Holy Spirit that early Christians were able to overcome both external challenges and internal shortcomings. While the difficulties we face today, as a church and more broadly, may be different, we are no less in need of the Spirit’s help as we continue to strive for justice for all people — with love, with hope, and with pride.

Patrick Haley, PhD, teaches theology at Princeton Theological Seminary. His work explores the intersection of ethics, religion, and queer experience, often focusing on queer reinterpretations of traditional Christian virtues to better serve LGBTQ+ persons and communities.