An Anniversary Week: Recalling Alexander Hamilton's Duel, Death & Funeral

Alexander Hamilton's life ended (at either age 49 or 47; historians are divided in their opinions) during the second week in July 1804. Hamilton was mortally wounded on Wednesday, July 11, he died July 12, and his funeral was held at Trinity Church Wall Street on July 14. Alexander Hamilton had a long association with Trinity, and rented a pew in the church, although it appears to have been his wife Eliza and the children who regularly attended worship. But at the very end of his life, as he lay bleeding and paralyzed in a house on Greenwich Street, he did call for the Rector of Trinity Church.

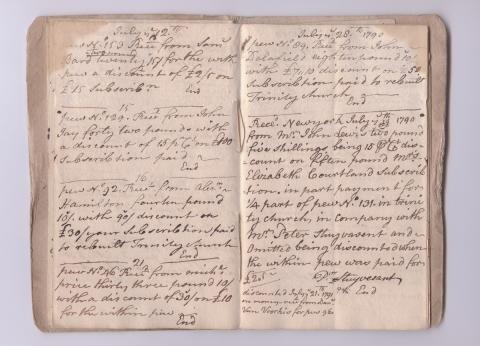

Pew book showing Hamilton's rental of pew 92 in Trinity Church

Alexander Hamilton played a larger-than-life role in defining the powers of the fledgling federal government: he was the founder of an early version of the Coast Guard, first Secretary of the Treasury, wrote more than 50 of the Federalist Papers, served as a constitutional lawyer, and campaigned for the establishment of the U.S. mint. In his private life, Hamilton served as a trustee of Kings College (later Columbia University), founded the Bank of New York, and chaired a citizens’ committee that created New York’s first water company.

But for all his modern accomplishments, Hamilton succumbed to an ancient vice: dueling. He died on the afternoon of July 12, 1804, of a gunshot wound suffered the previous day in a duel with Vice President Aaron Burr.

As hard as it is to imagine two such prominent statesmen settling a war of words through mutually-attempted murder, dueling was widely practiced in both Europe and America at the time. Dueling over political matters seems to have been a uniquely American invention. As a young man, Andrew Jackson killed a man in a duel. Button Gwinnett, second governor of Georgia and a signer of the Declaration of Independence, was killed in duel with a political rival.

Most clergy, including the priests at Trinity Church, opposed dueling, as did Benjamin Franklin and George Washington. Legal opposition to dueling had also formed, and the practice was outlawed in New York. None of this dissuaded Hamilton or Burr, who were longtime political enemies.

The Argument

The events that lead up to the duel began on April 24, 1804, as Burr was campaigning for the governorship of New York. The Albany Centinel published a letter written by Dr. Charles D. Cooper to Philip Schuyler, Hamilton’s father-in-law and prominent politician in his own right. The letter alluded to Hamilton’s “despicable” opinion of Burr, reportedly expressed at a political dinner the previous winter. When Burr read the letter, he wrote Hamilton demanding that Hamilton either admit or deny the alluded-to statements. Hamilton argued that he could not admit or deny a vague inference, responding in a letter:

Repeating that I can not reconcile it with propriety to make the acknowledgment or denial you desire, I will add that I deem it inadmissible on principle, to consent to be interrogated as to the justness of the inferences which may be drawn by others, from whatever I may have said of a political opponent in the course of a fifteen years competition.

After several more letters back and forth, Burr formally challenged Hamilton to a duel. Hamilton accepted.

In the days before the duel, Hamilton wrote two letters to his wife, Eliza Schuyler Hamilton, a devout member of Trinity Church.

My Beloved Eliza:

…This is my second letter. The scruples of a Christian have determined me to expose my own life to any extent rather than subject myself to the guilt of taking the life of another. This must increase my hazards and redoubles my pangs for you. But you had rather I should die innocent than live guilty. Heaven can preserve me and I humbly hope will; but, in the contrary event, I charge you to remember that you are a Christian. God's will be done! The will of a merciful God must be good.

The Duel

In the early hours of July 11, 1804, Hamilton boarded a rowboat with Nathan Pendleton, his second in the duel (a sort of standby and assistant), and Dr. David Hosack, his physician. They arrived at a popular dueling ground overlooking the Hudson River in Weehawken, New Jersey (dueling was illegal in New York at the time). Burr and his party were already there.

Hamilton took the northern position and bothmen readied their Wodgen & Barton dueling pistols. Dr. Hosack, the rowers, and most of Burr’s party remained in the boats so as not to witness the duel and open themselves to criminal prosecution. The only men present during the duel were Hamilton, Burr, and their seconds. Both men fired once, and Hamilton was struck in the abdomen, just above his right hip.

Hamilton's Final Hours

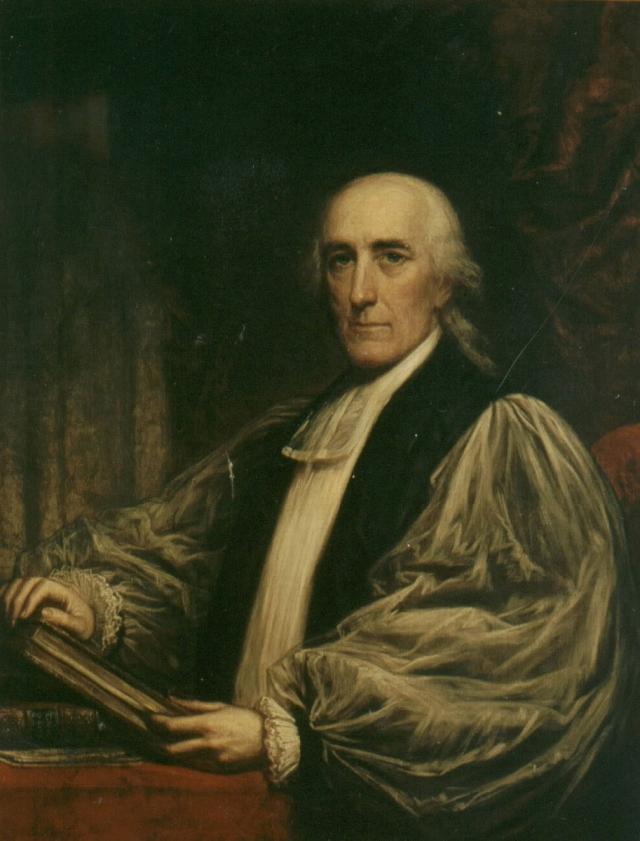

The Rt. Rev. Benjamin Moore

Hamilton was rowed back across the Hudson to the home of William Bayard, a friend. Hamilton requested that the Rt. Rev. Benjamin Moore, Rector of Trinity Church, Bishop of New York, and president of Columbia College, visit him. In a letter published on July 13, Moore described the events of the afternoon and evening of July 11:

Thursday Evening, July 12, 1804

Yesterday morning, immediately after he was brought from Hoboken to the house of Mr. Bayard, at Greenwich [modern day 82 Jane Street], a message was sent informing me of the sad event, accompanied by a request from General Hamilton, that I would come to him for the purpose of administering the holy communion, I went; but being desirous to afford time for serious reflection, and conceiving that under existing circumstances, it would be right and proper to avoid every appearance of precipitancy in performing one of the most solemn offices of our religion, I did not then comply with his desire. At one o’clock I was again called on to visit him. Upon my entering the room, and approaching the bed, with the utmost calmness and composure he said, “My dear sir, you perceive my unfortunate situation, and no doubt have been made acquainted with the circumstances which led to it. It is my desire to receive the communion at your hands. I hope you will not conceive there is any impropriety in my request.” He added “I was for some time past been the wish of my heart, and it was intention to take an early opportunity of uniting myself to the church, by the reception of that holy ordinance.”

…I then asked him, “Should it please God to restore you the health, sir, will you never be again engaged in a similar transaction? And will you employ all your influence in society to discountenance this barbarous custom?” His answer was, “That, sir, is my deliberate intention.”

I proceeded to converse with him on the subject of his receiving the Communion; and told him that with respect to the qualifications of those who wished to become partaker of that holy ordinance, my enquiries could not be made in language more expressive than that which was used by our Church—“Do you sincerely repent of your sins past? Have you a lively faith in God’s mercy through Christ, with a thankful remembrance of the death of Christ? And are you disposed to live in love and charity with all men?” He lifted up his hands and said “With the utmost sincerity of heart I can answer those questions in the affirmative—I have no ill-will against Col. Burr. I met him with a fixed resolution to do him no harm—I forgive all that happened.”

…The Communion was then administered, which he received with great devotion, and his heart afterwards appeared to be perfectly at rest. I saw him again this morning, when with his last faltering words he expressed a strong confidence in the mercy of God through the intercession of the Redeemer. I remained with him until 2 o’clock this afternoon, when death closed the awful scene—he expired without a struggle, and almost without a groan…

The Funeral

Moore’s letter was reprinted in newspapers across the country. On July 14, Hamilton’s funeral was held at Trinity Church. Gouvernor Morris, a close friend of Hamilton, gave the funeral address “on a stage erected in the portico of Trinity Church, having four of General Hamilton’s sons, the eldest about sixteen and youngest about 6 years of age with him.”

Alexander Hamilton was buried near the southern fence of Trinity churchyard. Today, his monument towers over the simple vault stone of his wife, Eliza. And somewhere in Manhattan, possibly very nearby, lay the bones of their eldest son Philip, killed in a duel three years before his famous father.

Postscript

Dr. David Hosack went on to have several children, including sons named Nathanael Pendleton Hosack and Alexander Hosack. Alexander Hosack followed in his father’s footsteps and became a prominent physician, tending to Aaron Burr in his final years. According to Alexander Hosack’s 1871 obituary in the New York Times, he once asked Burr if he felt any remorse over Hamilton’s death. Burr reportedly said that he suffered no remorse, and that Hamilton had brought his death on himself. Nathanael Pendleton Hosack was a Vestryman at Trinity Church.

Both Alexander Hosack and Nathanael Pendleton Hosack are buried uptown at Trinity Church Cemetery and Mausoleum.

Don't miss this video tour of Hamilton's involvement at Trinity Church: visit the graves of Eliza, Angelica, Hercules Mulligan, and Alexander himself, view documents revealing Hamilton's spiritual and legal connections to the parish, and learn about the second Trinity Church building that Hamilton's family attended.