Yes, There is Treasure Underneath Trinity Church

Years after the hit movie National Treasure was released, Trinity docents are still asked if there is treasure under the church. Usually the answer is no, but Trinity’s rejuvenation efforts may cause tour guides to adjust their scripts.

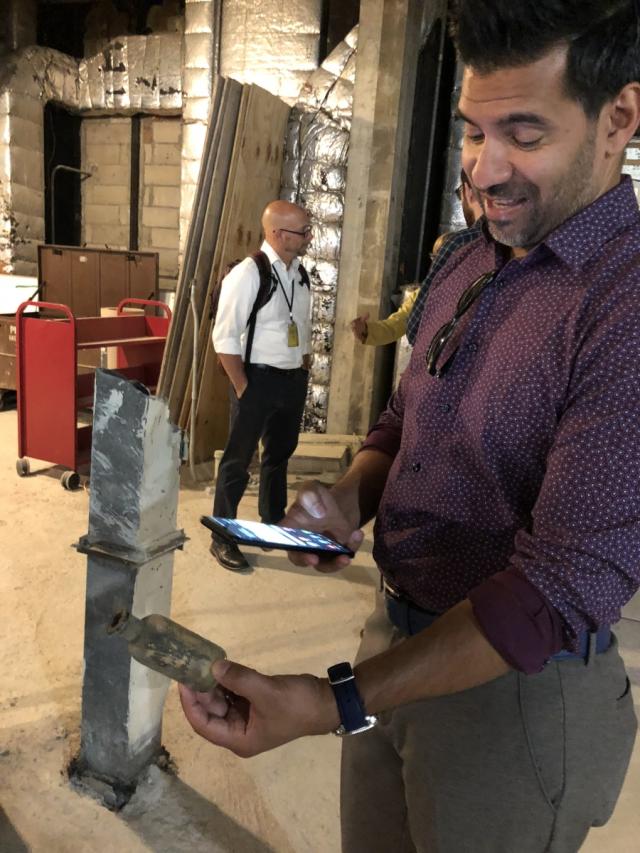

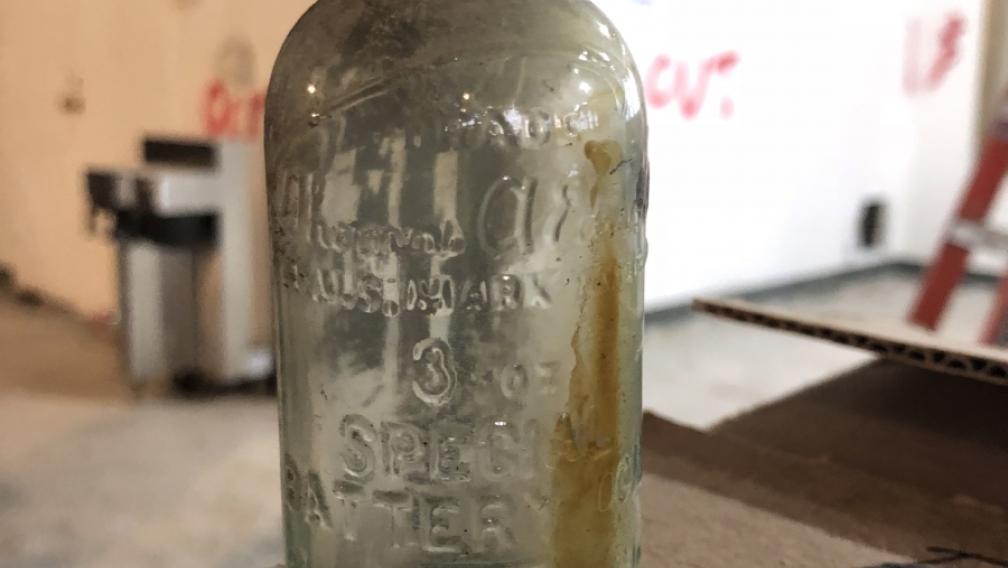

At a recent tour of the rejuvenation work in Trinity Church, Senior Construction Project Manager Luke Johns introduced the group to a bottle found under the flooring on the north side of the main altar. Molded in green-tinted glass, the bottle was made to hold three ounces of “Special Battery Oil,” manufactured by the Thomas A. Edison Company in Orange, New Jersey.

This discovery came just a few weeks after a shoe and a German-language newspaper from the 1870s were found when the altar was moved from the west wall which supports the Astor reredos.

It’s not gold, but a quaint, intact bottle with clear lettering is a fascinating, even mysterious, object. A quick Google search and perusal of collectors’ websites tell us Edison’s company changed names from Edison Manufacturing Company to Thomas A. Edison Inc. in 1911, and a fire at the Orange plant caused the operation to move to Bloomfield, NJ, in 1915. That places our bottle between 1911 and 1915.

Construction of Trinity’s Chapel of All Saints began around 1910, and the chapel was consecrated in 1913. Given the bottle’s resting place and time period, could it have been used in the construction of All Saints? Probably not, since the chapel was added to the church’s exterior rather than including work inside the church where the bottle was found.

A clipping from the February 7, 1916 edition of The New York Times describes the new chancel furniture donated by Louis V. Bell.

A little more digging through Trinity records and newspaper clippings offer a more likely answer. Trinity’s archives tell us parishioner Louis V. Bell (1853-1925, a member of the New York Stock Exchange, race horse owner, and art collector) donated a new set of chancel furniture to Trinity Church in 1916. There aren’t many documents about the work, but a notice in The New York Times about the dedication tells us Bell’s gift included stalls for clergy and choir members, an altar rail, and marble paving. It’s a good guess that the installation of the new furniture and flooring resulted in this bottle’s 100-year resting place.

We now know when and likely how the bottle came to Trinity, but what did “special battery oil” do?

In the early part of the 20th century, Thomas Edison developed the nickel-iron battery, which he hoped to use for electric automobiles. Before the batteries could be perfected, gasoline became the fuel of choice for cars, so Edison’s batteries were used to power railroad switches, signal boxes, and lamps used in mines.

Trinity Archivist Joseph Lapinski says batteries using the oil could have powered lights or other equipment during construction.

The batteries were made of a glass or ceramic container with iron and nickel plates and an electricity-conducting solution of caustic soda and water. Oil was poured over the plates and solution, where it would rise to the top and form a seal over the liquid that prevented the water from evaporating too quickly and helped the battery hold its charge longer. Over time, the elements would need replenishing, and workers periodically topped off the containers with more soda, water, and oil.

It seems workers didn’t like carrying empty containers around, because decades later collectors still find bottles near railroad crossings where the batteries were used. Workers undertaking Trinity’s rejuvenation, and those of us monitoring their progress, are glad to share in these collectors’ delight.

Senior Construction Project Manager Luke Johns photographs the bottle, one of several items found during recent work in Trinity’s chancel.