Unearthing Our Past

That New York City was once home to the largest urban community of slaves outside Charleston, South Carolina, was largely unrecognized until 1991, when the construction of a federal building near City Hall exposed the remains of more than 400 enslaved and free colonial-era blacks. When it appeared building was to proceed as planned, a civic meeting was held in Trinity Church for people to voice their grievances. Eventually, organizations fighting for recognition of the role played by those of African descent in the emergence of New York City succeeded in having architectural plans altered, and were awarded $3 million for the creation of a memorial. The exhumed remains were sent to Howard University, in Washington D.C., for study.

This fall, in commemorations stretching over five days, the remains were ceremoniously transported from Washington back to the new African Burial Ground memorial in New York. Dignitaries and celebrities including Mayor Michael Bloomberg were present as caskets were brought ashore from a barge at the point where Wall Street meets the East River - site of the city's first slave market during British rule. Then men dressed in colonial attire pounded drums as a colorful procession, including hand-carved coffins drawn by horses, was brought to Broadway and through the "Canyon of Heroes" for reburial the following day.

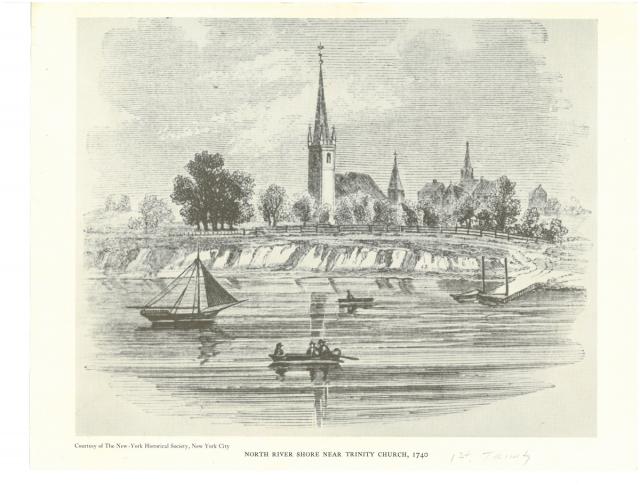

There was a moment of historical synergy between the cortege and Trinity, when the church - the only community institution along the route that had existed when the Africans in those coffins had been alive - tolled its bells as a sign of respect as the procession passed by. The event begged the question: what was Trinity's relationship to slavery in New York?

Parish archivist and historian Gwynedd Cannan examined the records and produced this report.

This article, based almost entirely on documents in the Trinity Church archive, will not totally answer the questions regarding Trinity's response to slavery. But it demonstrates that evidence exists which, studied in the context of the wider church and community, can help focus an unfamiliar time in our city's history.

The use of slave labor

An examination of records, from the church's beginnings in 1696 to the abolition of slavery in New York State in 1827, demonstrates that the parish enlisted slave labor in the building of its first church, catechized and ministered to Africans and persons of African descent, enslaved or free, and practiced a fluid burial segregation in its churchyards.

In 1696, a group of New York City laymen purchased land belonging to the Lutherans at what is now Wall Street and Broadway for the purpose of building an Anglican church. They began meeting together formally in January 1696 "to Consult of ye most Easy Methods in Carrying on the building of a Church for the Protestants of ye Church of England." In the first meeting, twelve members were appointed managers to oversee construction. The managers kept scrupulous minutes throughout the year detailing how the funds were raised and expended.

The minutes specifically mention the use of enslaved labor at several points. Four of the managers each "lent a Negro" to dig the foundation and the twelve managers were each designated to provide "A Negro or Labourer" to work fourteen days on the building at their own cost over and above what they contributed to the subscription. It would seem that most, if not all, of the managers were slave holders, although the "Negro or Labourer" phrase implies that if some managers owned no slave or could make none available, they were still responsible for providing a workman. In May, the managers again decreed that "each member present . . . send a Negro" for work on the foundation.

The managers contracted with masons and carpenters for the main body of work. The archives contain a contract with the master mason, Derick Vanderburgh, dated June 3, 1696, that required that Mr. Vanderburgh supply four masons and that "Saml Van de burgh is to furnish sd managers for use of Trinity Church three Labourers viz Jack his own Negro, Jack Jaman's Negro and ye Negro belonging to the French minister at three shillings per diem." The contract with the carpenters has not been found but it is presumed that their arrangement would be similar.

The first Trinity Church building was burned down in the Great Fire of 1776, and was rebuilt between 1788 and 1790, while slavery was still legal in New York. The Vestry minutes describe how money was raised through subscriptions but never specifies whether enslaved persons, paid or not, were employed. Nor have contracts or other documentation been found for the second church building. The rebuilding was costly and the minutes reveal that lots from the Church farm - a large parcel of land granted to the Church in 1705 by Queen Anne - had to be sold to make up the difference between the total rebuilding cost and the amount raised by subscriptions.

Catechizing and Education

The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) was established in 1701 to evangelize throughout British-occupied territories. Elias Neau, a French Huguenot and cloth merchant, urged the SPG in 1704 to appoint a catechist for the numerous Africans in New York City. When the Society offered its support, Neau himself took over the duties.

Neau's classes were later blamed for a violent uprising of slaves that occurred in 1711. He was able to continue teaching, but in 1713 a law passed forbidding slaves from walking outdoors at night with a lantern or candle. This was taken by some to be a way to discourage blacks from attending Neau's school since classes had to be held at night when the slaves could get away from their chores.Neau at first met hostility from slave owners as he sought to enlist students, but the SPG urged the authorities to support his efforts. A law was enacted in 1706 to assure slave owners that Baptism and catechizing would not interfere with property rights, noting that owners were "deterred by reason of a Groundless opinion that hath spread itself in this Colony that by the Baptizing of such Negro, Indian or Mulatto slave they would become free and out to be sett at Liberty."

Neau died in 1722 and catechization continued through the SPG under the auspices of Trinity Church. The Vestry minutes include an informative letter written July 5, 1726 that reported:

About one Thousand and four hundred Indian and Negro slaves and the number daily encreaseing by Births and importation from Guiney and other parts. A considerable number of those Negroes by the Societys Charity have been already instructed in the principles of Christianity, have received Holy Baptism Are communicant of our Church and frequently approach the altars....Since Mr. Wetmores appointment we have with great pleasure observed on Sundays upwards of an hundred English Children and Negro Servants attending him in the Church and their catechetical Instructions being ended singing psalms and praising God with great devotion.

The success of the American Revolution ended the authority of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in the New World, but Trinity Church continued its work among black New Yorkers.

In 1785, the New York State Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves was organized to lobby for anti-slavery laws and to assist African-Americans, slave and free. John Jay, Trinity churchwarden from 1785 to 1790, who became the first chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court and then governor of New York, was president of the society. Trinity pew holder, and first Secretary of the U.S. Treasury, Alexander Hamilton was also a member.

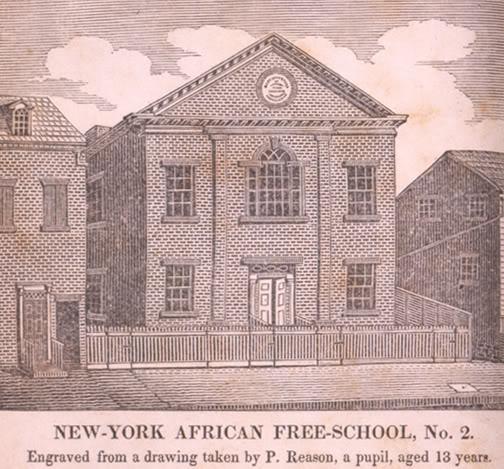

In 1787, John Rodgers represented the Manumission Society in a petition to the church for land to build a school. Trinity provided the land behind St. George's Chapel, which was also located in downtown Manhattan. By May 1814, the African Free School was said to be teaching 100 children.

Trinity also helped Peter Williams, Jr., who was establishing an "Episcopal School for the instruction of coloured youths," according to a letter to the Vestry dated November 1815.

The minutes record at one point that instruction of Africans in the Word of God "will be a vast accession to their future happinness and encrease their rewards of Glory in another World." It appears that we saw our role as tending to the souls of New York's inhabitants and that while we dispensed charity and education to the impoverished, we pointed to the next world for injustices to be righted.

Burial Segregation

It has been suggested in recent years that the founding of a segregated African Burial Ground outside the city limits was a consequence of prohibitions on the burial of people of African descent in Trinity's churchyards. Although Trinity did introduce formal policies restricting such burials, and helped to establish segregated burial grounds, our archives reveal a more nuanced and complex picture: not only do the prohibitions appear to have been implemented unevenly, but the parish's formally declared policy made provision for burying slaves in parish churchyards if they were communicants.

England took New Amsterdam from the Dutch in 1664, renaming it New York. After Trinity was established and began taking control of land in Lower Manhattan in 1697, one of its actions was to take over existing public burial grounds. On July 3, 1697, the vestry gave notice to drivers and haulers "That noe Carmen shall after notice given Digg or carry away any ground or Earth from behind the English Church & burying ground."

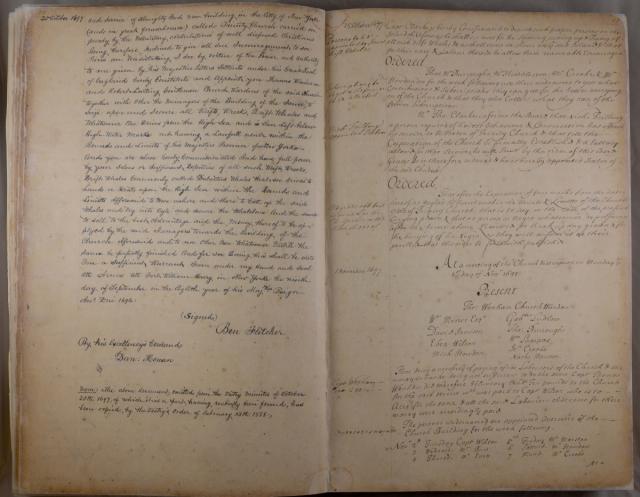

The following resolution appeared in the vestry minutes of October 25, 1697:

That after the Expiration of four weeks from the dates hereof no Negro's be buried within the bounds & Limitts of the Church Yard of Trinity Church, that is to say, in the rear of the present burying place & that no person or Negro whatsoever, do presume after the terme above Limitted to break up any ground for the burying of his Negro, as they will answer it at their perill & that this order be forthwith publish'd.

This interdict followed a statement on the hiring of the first sexton, who was the person responsible for breaking burial ground and receiving the requisite fees. The prohibition against any "person or Negro" burying "his Negro" implies that the resolution is addressed to slave owners (probably non-Anglican) who were burying (or having others bury) their slaves behind the public burying ground. Allowing four-weeks notice suggests that the new rule was breaking a long custom, but it is to be "forthwith publish'd" allowing time to broadcast the new rules so that none can plead ignorance.

The churchyard referred to in the 1697 interdict did not include an old burial ground to the north of the church (which is now Trinity's north churchyard). Trinity didn't petition for this land until 1703, when it pointed out to the city that fees for burial were still being paid to the Dutch Church, the established Church of the former government, and said it seemed more fitting that the burial ground and the attendant fees should be handed over to the church that practiced according to the rites of the Church of England. The city granted the Church the public burial ground on April 22, 1703.

Seventy years later, Trinity's vestry resolved to designate a piece of the Church Farm as a "Burial ground for the Negro's." The spot chosen was bounded by Church Street, Reade Street, Chapple Street (West Broadway), and "Anthony Rutgers' land." The lot was located a few blocks west and directly parallel to the current African Burial Ground memorial site: both were outside the new city limit, about half a block north of Reade Street.

By May 27, 1784, the Trinity churchyard was so crowded with burials that it was difficult to inter new coffins. Burials were being dug only three feet deep. Consequently, the vestry restricted burials to people whose family members were already interred in the Trinity churchyard, and to vaults. On October 20, 1787, the minutes contain an order that a charnel house was to be built in Trinity churchyard, ostensibly to take up bones of graves no longer visited.

On April 12, 1790, the vestry minutes again banned burials of African-Americans, ordering "that in future no black Persons be permitted to be buried in Trinity Church Yard, nor any except Communicants in the Cemetery at St Paul's." The wording of the ban implies that African-Americans had continued to be buried both at Trinity and St. Paul's, in spite of the 1697 ban and in spite of the burial ground set aside specifically for black burials in 1773. In the 1790s, the public African Burial Ground and the Trinity African Burial Ground closed, probably succumbing to the northward push of city development. But the parish was involved in the ensuing establishment of another segregated burial ground: in 1795, Isaac Fortune and "other Free Black persons" petitioned the parish for funds to help them "purchase a piece of Grounds as a Burial place to Bury Black persons of Every denomination and Description whatever in this City whether Bond or Free." Trinity responded affirmatively and a new African burial ground was situated on 195/197 Christie Street.

A later petition to the vestry by Peter Williams, Jr. of St. Philip's Church sheds some light on the transaction. In November 8, 1826, Williams was requesting Trinity's help in possessing the Christie Street burial ground for St. Philip's Church. The letter establishes the history of the burial ground that was "purchased by the African Society many years since for a burial ground for coloured persons, and with a view of erecting thereon at some future period an Episcopal Church. This Society was originally composed of about thirty coloured Episcopalians, but has become so diminished in numbers by the decease of its members that there are but five remaining." The deed for the burial ground had been held in trust until the African Society "should become incorporated as a religious body." Peter Williams requested that St. Philip's receive the deed "as the members of this Society were at first all Episcopalians and as all the survivors are members of St. Philip's Church."

The vestry resolved to level Trinity's "Negro Burial Ground" on August 19, 1795. By 1797 the lots into which the burial ground had been divided were leased. In the minutes of 1801, the vestry resolved that the children of black communicants "may be buried in the Cemetries of the Several Churches" (Trinity and the chapels of St. Paul and St. John). The Trinity Church burial registers show that between 1801 and 1818, fourteen persons of color, aged from six months to 83 years at the time of death, were buried at both Trinity Church and St. Paul's.

By 1822, the question was moot as all burials in Lower Manhattan were forbidden.

Posted on Trinity News, February 13, 2004

Recommended Video