They Parted in Mutual Sorrow

January 14, 2013

January 4th is the feast of Elizabeth Seton, remembered primarily as the first American-born Roman Catholic saint. She was a longtime member of Trinity Church.

The letter arrived on the desk of Dr. Fleming, Trinity’s rector, in 1947. The Vatican was requesting access to Trinity’s archives in search of an elusive document: the baptismal record of Elizabeth Seton--the same Elizabeth Seton who would be canonized in 1975, the first American-born Catholic saint.

It’s fitting that the road to sainthood for Seton wound through Trinity Church because it began there. Seton lived to be 46 years old; for thirty of those years she was a devout communicant of Trinity Parish. Her decision to convert to Catholicism was so wrenching for her dear friend, the Rev. John Henry Hobart, an assistant minister at Trinity and the future Bishop of New York, that his biographer would single it out as “an event that long rested on his memory with painful interest.”

Elizabeth Anne Bayley was born into a prominent Anglican family with many connections to Trinity Church on August 28, 1774. Little Eliza Anne, as she was known, was certainly baptized soon after her birth, though no records of when or where the ceremony took place survive.

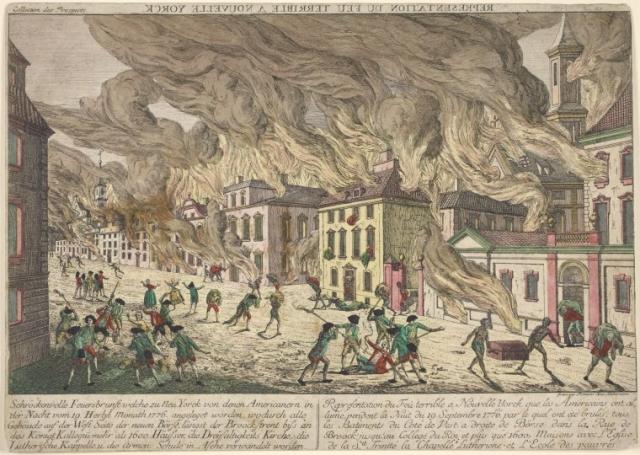

It’s difficult to imagine the Lower Manhattan of Seton’s childhood---a city half-burnt by the Great Fire of 1776, occupied by the British Army, and continuously besieged by infectious disease. Seton’s mother died when she was two years old, likely in childbirth. Her father’s remarriage to the young Charlotte Barclay, a fellow Trinity parishioner, produced seven children before ending acrimoniously.

The Great Fire of 1776

Seton’s early writings reveal an intense, emotional relationship with God. The spires of Trinity Church and St. Paul’s Chapel, visible from Staten Island and Lower Manhattan, were her happy symbols of faith and home.

On a Sunday evening in January, 1794 Eliza Anne Bayley married William Magee Seton, the son of a successful merchant family. The Setons settled into a comfortable family life and soon had five children. Even in the midst of temporal joy, Seton sensed God’s presence, writing soon after her marriage, "My own home at twenty - the world - that and heaven too." Always active in charitable works, Seton helped found the Society for the Relief of Poor Widows with Small Children in 1797 and taught children’s catechism for Trinity Parish.

In 1798, William Seton’s father died, leaving the young couple to raise his seven orphaned siblings, including his younger sister Rebecca, who became Seton’s best friend and “soul sister.” The death of her father-in-law began a period of trial in Seton’s life. William’s business struggled, and he contracted tuberculosis. But one bright spot appeared in Seton’s life in September,1800: a young assistant minister named John Henry Hobart arrived at Trinity Church.

When they met Hobart was just 24 and an unusually enthusiastic preacher. Seton, then 26, was entranced by his sermons. “Mr. Hobart this morning--language cannot express the comfort the Peace the Hope,” she wrote in a letter to Rebecca that year. Hobart preached a “high church” theology, emphasizing, among other things, the importance of the Eucharist in spiritual life.

Seton’s letters reveal the depth of her friendship with Hobart, on whom she relied during this difficult period in her life. Hobart was also struggling, and he sought out Seton for comfort. Early in 1801, he called on Seton at her home after returning from a visit with his ailing mother and sister in Philadelphia.

“Mr. H[obart] sent up to know if we were all well. I went down quietly as possible but trembled rather too much even for a Christian--told me a great deal about his mother and sister.”

Then Seton told Hobart of her great joy: her husband, William, had experienced a religious awakening, an event Seton attributed to Hobart’s influence.

“I told him the last 24 hours were the happiest I had ever seen or could ever expect as the most earnest wish of my heart was fulfilled…if you had known how sweet last evening was--Willy’s heart seemed nearer to me for being nearer to his God.”

Later in 1801, Seton sent a letter to a friend in which she talked of Hobart:

“The soother and comforter of the troubled soul is a kind of friend not often met with…he is so the friend most my friend in this world, and one of those who after my Adored creator I expect to receive the largest share of happiness from in the next.”

Hobart’s friendship buoyed Seton through her father’s death in 1801, and into a difficult 1802 and 1803. William’s health deteriorated as his faith, encouraged by Hobart, grew. William was forced to declare bankruptcy and the family lost their home.

In October 1803, the Setons and their eldest child, Anna Maria, set sail for Italy. William had friends there and hoped that a change in climate would restore his health. Seton carried her “hidden treasure” across the ocean: religious books and copies of Hobart’s sermons.

When the family arrived in Italy they were immediately quarantined for a month, “shut up in damp walls, smoke, and wind.” As William neared death, Seton’s soul soared towards God and home. “I went to sleep,” Seton wrote in a journal addressed to Rebecca, “and dreamed I was in the center Isle of Trinity Church, singing with all my soul the hymns at our dear sacrament.”

Though thousands of miles away, Hobart was a presence in the darkest hours of Seton’s life. “I sometimes feel that his angel is near and undertake to converse with it.”

William died on December 27, 1803.

Seton and Anna Maria stayed in Italy for several months, cared for by William’s friends, the Filicchi family. “Tell my dear friend John Henry Hobart that I do not write because the opportunity is unexpected and my breast is very weak after all its struggles,” she wrote on January 4, 1804. “That I have a long letter I wrote on board of ship to him--that I am hard pushed by these charitable Romans who wish that so much goodness should be improved by a conversion.”

By the time Seton left Italy, she was seriously considering Catholicism. Transubstantiation--the doctrine of the real presence of God in the bread and wine at the Eucharist--was irresistible to her. “My sister dear,” she wrote to Rebecca, “how happy would we be if we believed what these dear Souls believe that they POSSESS GOD in the sacrament?”

Seton drafted a letter to Hobart on the ship home. “The tears fall fast thro’ my fingers at the insupportable thought of being Separated from you …I cannot doubt the Mercy of God who by depriving me of my dearest tie on earth will certainly draw me near to him.”

Back in New York, Seton, now an impoverished single mother, spoke openly to Hobart about her belief in Catholicism. Hobart spent months trying to counsel her out of conversion, insistent that the Anglican Church was the true successor to Christ and his apostles. Their friendship deteriorated, as neither was able to come to terms with the other’s point of view.

“Mr. H. was here yesterday…and was so intirely out of all patience… his visit was short and painful on both sides—God direct me for I see it is in vain to look for help from any but him“

Ironically, Seton seems to have made peace with her decision to convert during services in St. Paul’s Chapel in September 1804: “I got a side pew which turned my face towards the Catholic Church [St. Peter’s] in the next street, and found myself twenty times speaking to the Blessed Sacrament there instead of looking at the naked altar where I was…Mr. H. says how can you believe that there are as many gods as there are millions of altars and tens of millions of blessed hosts all over the world—again I can but smile at his earnest words, for the whole of my Cogitations are but reduced to one thought it is GOD who does it.”

St. Paul's Chapel during the nineteenth century.

Ash Wednesday 1805 was “a day of days” in Seton’s life. “I have been—where—to the church of St. Peter with a CROSS on the top instead of a weathercock.” Her joy was tinged with the knowledge of what she turned her back on: St. Paul’s Chapel and Trinity Church, whose weathervane-topped spires long represented her spiritual home.

From that day forward, Seton was a devout Roman Catholic. Hobart’s biographer, who knew and worked with the man, said it well, “They parted, however, not in anger, but mutual sorrow, each to run the course of a high and conscientious duty.” Hobart became an influential Bishop of New York, celebrated with a feast day in the Episcopal Church. Seton took holy orders and founded the Sister of Charity, which still exists today.

When she was confirmed in the Roman Church, Seton’s Episcopal baptism was considered sufficient and she was not re-baptized.

Seton was canonized on September 14, 1975. The Rev. Hunsicker, longtime vicar of St. Paul’s Chapel, attended as a guest of the Vatican, and a special Eucharist was celebrated in Trinity Church. Perhaps Elizabeth Seton and John Henry Hobart, reunited in the next life as Seton once hoped, looked down.