The General and The Monument

During the rejuvenation of the nave of Trinity Church, 11:15am Sunday Holy Eucharists are held in St. Paul's Chapel, site of the monument to General Richard Montgomery, who was interred 200 years ago this Sunday, on July 8, 1818.

The monument to General Richard Montgomery is fixed to the east window of St. Paul’s Chapel, facing Broadway. Tourists, over a million a year, pass into the Chapel without pausing to read its inscription. Commuters and neighborhood residents scurry down Broadway, many oblivious to the monument, unaware of the role General Montgomery played in the founding of the United States.

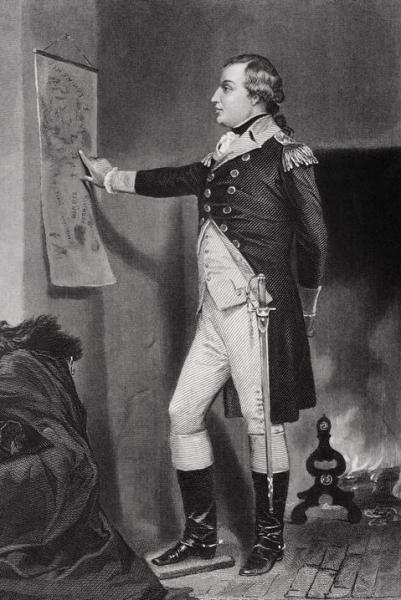

THE GENERAL

Richard Montgomery was born into a family of landed gentry in Ireland in 1738. He studied at Trinity College and joined the British army when he was 18. In 1757, during the Seven Years War, his regiment was sent to Canada to help force the French out of North America. Montgomery spent the next eight years in North America, taking part in successful British campaigns in Canada, the French West Indies, Cuba, and against Pontiac’s Rebellion. He was promoted from ensign to captain during that time.

Montgomery returned to England in 1765 and found life in the peacetime army difficult. Lacking a wealthy or influential patron, he was unable to rise through the military ranks. He became increasingly dissatisfied with the British government. In 1772, he sold his commission in the army and migrated to America.

In America, Montgomery purchased an estate and married into a family of prominent New York patriots, planning the quiet life of a gentleman farmer. In 1775, though he did not seek office, Montgomery was elected to New York’s Provincial Congress, and later entered the new Continental Army as a brigadier general. Montgomery would now fight against the British army in which he once served.

George Washington assigned Montgomery the role of deputy commander under Major General Philip Schuyler, and ordered their forces to invade Canada. Schuyler soon fell ill, leaving Montgomery in full control of the operation. Montgomery oversaw the successful siege of Fort St. Jean and the capture of Montreal in the fall of 1775. He was promoted to major general as a result of these victories, though he never learned of his promotion.

Montgomery and his troops then marched on Quebec. On December 30, in a heavy snowstorm, Montgomery led an advance force into the city and was killed by grapeshot. He was given an honorable burial by British commanders in Quebec.

THE MONUMENT

Patriots quickly seized upon the story of Montgomery’s life--and his heroic death-- to build support for separation from Britain. Poems lauding his exploits were published in colonial newspapers, and an anonymous propagandist published “Dialogue between the Ghost of General Montgomery Just arrived from the Elysian Fields; and an American Delegate, in a Wood Near Philadelphia,” in which the specter of Montgomery urges revolution.

On January 25, 1776, Congress approved creation of a memorial for Montgomery—the first monument ever commissioned by the United States. Benjamin Franklin, who would oversee the monument’s construction in France, was advanced 300 pounds sterling to cover the costs (about $45,000 today).

Franklin commissioned Jean-Jacques Caffieri, official sculptor of the French crown, to create the monument, originally intended for Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. The monument, minus inscription, was shipped to America in nine lead-sealed cases, with a manifest and specific directions for installation included. (These facts were recently uncovered by Professor Sally Webster, author of The Nation's First Monument and the Origins of Public Commemoration in America.)

CAFFIERI

Because of the war and its chaotic aftermath, the monument spent nearly a decade languishing in transit, first in Le Havre and later in Edenton, North Carolina, the only American port not controlled by the British at the time of its shipment. Franklin was unaware of its location, and wrote letter after letter seeking information on its whereabouts.

In 1784, Charles DeWitt, a member of New York’s delegation to Congress, introduced a resolution that the monument be erected in New York City. But it wasn’t until 1787 (and several more letters from both Franklin and Montgomery’s widow) that the Common Council of New York recommended that the monument be installed in “the front of St. Paul’s Church.” St. Paul’s Chapel was likely chosen for its architectural and cultural significance to the young city—it was the grandest building in town.

Trinity’s vestry and wardens, including then-Mayor James Duane, quickly approved the request. By June of 1788 it had been installed in St. Paul’s Chapel, likely under the direction of Pierre L’Enfant. L’Enfant, who later designed Washington, DC, was working on small engineering projects for the city at the time

There is no record of a dedication ceremony for the monument.

L’ENFANT’S CONTRIBUTION

While the monument was a stunning addition to the chapel’s exterior, the back of the monument marred the east window of St. Paul’s when viewed from inside the church. L’Enfant designed a wooden sculpture to mask the monument’s back. Seen from outside, the sculpture outlines Caffieri’s work with “an eagle [drawing] back the American flag from the Western Hemisphere, which is illumined by the 13 rays of the rising sun, while below a weeping cupid among the clouds with inverted torch mourns the hero who fought for this new found world of freedom.”

The other side of L’Enfant’s sculpture, the side visible from inside the chapel, is a depiction of the giving of the Ten Commandments.

THE MONUMENT BECOMES A TOMB

The war of 1812 brought a renewed interest in Montgomery’s story. In 1818 Montgomery’s widow Janet was able to persuade the New York State legislature to authorize moving Montgomery’s remains from Quebec to a tomb below his monument at St. Paul’s Chapel.

Montgomery’s remains lay in state in the capital building in Albany on July 4, 1818. They were then placed on a steamboat for the journey down the Hudson River.

In General Richard Montgomery and the American Revolution: From Redcoat to Rebel, author Hal. T. Shelton describes what happened as the steamship carrying Montgomery’s remains passed the home of his widow:

Governor Clinton had notified Janet of the time when the [steamboat] Richmond would pass Chateau de Montgomery, and she went out on the veranda to view the ship carrying her general home. Forty-three years had elapsed since she and Montgomery parted at Saratoga. When pangs of nostalgia rushed over her, she requested to be left unattended on the porch. “At length, they came by,” she described the scene, “with all that remained of a beloved husband, who left me in the bloom of manhood, a perfect being.” The Richmond stopped, while a military band on board played the dead march and honor guard fired a salute, and then solemnly continued its passage to New York City. Emotions overcame the seventy-four-year-old widow. When her companions came to find her some time later, they found Janet unconscious on the floor where she had fainted.” (pp. 179-180)

Montgomery’s remains were re-interred at St. Paul’s Chapel on July 8, 1818, amidst great fanfare.

RESTORATION

A complete restoration of the Montgomery monument was undertaken by Trinity Wall Street in the late spring of 2011. After 224 years of New York weather, the iron pins that held the monument to the window had oxidized, and the expanding rust had cracked the stone in many places. Integrated Conservation Resources (ICR) restored the monument.

Trinity’s archives make reference to several repairs to the monument. Though not noted in records from the time of the monument’s installation, the monument’s original marble urn, visible in St. Alban’s etching made in France prior to the monument’s shipment, never made it to New York. A painted wooden urn, possibly designed by L’Enfant, was used until 1810 when it was replaced with a limestone urn. Mortars were used to patch the monument.

Conservators from ICR began by studying the monument to determine how it was attached to the window. Researchers studied Trinity’s archives and consulted Professor Sally Webster to gain a fuller understanding of the monument’s history. Then, the restoration—and the fascinating discoveries--began.

First, a barrier wall was constructed around the monument.

Next, the mortar used to repair cracks in the monument was painstakingly removed. Diamond-encrusted tools were used to separate the component pieces of the monument.

The nine pieces of the monument were removed, one at a time, from the window, revealing the monument’s original support structure.

One inch square metal rods, set into rough red bricks, supported iron pins that cantilevered the stones in place. The metal rods were found to be in pristine condition. Because the support structure extends through the window, tar-soaked oakum was used to create a watertight barrier around the monument.

And, most fascinatingly, the original installers—hoping to slow the monument’s deterioration--had poured molten lead around the iron pins, hoping to keep water out. The lead also created a buffer between the oxidizing pins and the stones: rust could expand into the malleable lead before cracking the rock.

Dismantling the monument also revealed a portion of the marble that had been hidden by another stone for 224 years. Still in its original condition, this bit of hidden marble reveals that the monument was once highly polished and black-and-red.

Historians, leading architects, and stone experts visited the monument.

Once separated, each stone was cleaned, removing all traces of earlier repair work, including paint splatter, repair mortar, and a protective coating that was applied to the entire monument at one time. Conservators also removed metal from the stones to prevent further corrosion.

The Montgomery Monument, early 1900s

DISCOVERY

While looking through old photographs of the monument, the team from Integrated Conservation Resources realized that photos from before the 1920s show parts of the monument broken and missing that are currently intact.

Look closely at the upper-right area of the monument. In this early twentieth century photo (dated by the type of window glass behind the monument), both arrows are missing. Notice the bottom-left area as well: the sculpture truncates at a strange place.

Sometime after the late 1920s

Shots from after the 1920s general restoration of St. Paul’s Chapel show a repaired monument. Intriguingly, the side portions of the monument, seen here being cleaned, are intact and show no signs of having been repaired. Were the side portions of the monument replaced in the 1920s?

It's very possible. Professor Sally Webster, author of Nation's First Monument and the Origins of Public Commemoration in America recently discovered sculptor Jean-Jacques Caffieri's original packing list for the monument. The packing list, which was sent to America with the monument, lists the side portions of the monument as being made of marble.

The current side portions are limestone.

Trinity’s archives yield one piece of hard evidence. A 1929 cost estimate for repair and waterproofing of all of St. Paul’s exterior stone surfaces includes a reference to repairing any “cracks or broken parts” of the “Marble Statuary” on the Chapel’s East Portico—seemingly a reference to the Montgomery Monument. It’s very possible that the side portions were replaced.

The restored monument

REASSEMBLY

Prior to reassembly, cracks in the monument were repaired using mortar made from an eighteenth-century recipe. The marble obelisk and column were polished, revealing their original color and shine.

The base of the monument’s column was too badly damaged to repair, and was replaced with a piece of marble from an Italian quarry. (The French quarry where the monument’s original marble was excavated closed many years ago.)

New stainless steel pins were used to attach the monument to the original support structure.

On August 10, 2011, the restored Montgomery Monument was unveiled.