Episcopal Saint: Remembering Pauli Murray's Life and Work

Liberating God, we thank you most heartily for the steadfast courage of your servant Pauli Murray, who fought long and well: Unshackle us from bonds of prejudice and fear so that we show forth your reconciling love and true freedom, which you revealed through your Son our Savior Jesus Christ; who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen. – Collect from Holy Women, Holy Men.

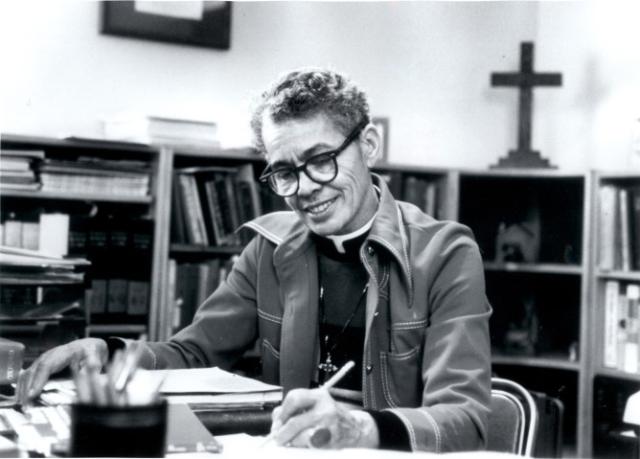

“When my brothers try to draw a circle to exclude me, I shall draw a larger circle to include them.” The Rev. Pauli Murray wrote these words in 1945, when she was already a pioneering lawyer and activist, but long before she became the first African-American woman ordained in the Episcopal Church.

Though she was writing about segregation, the words continue to resonate today. An activist, priest, nonconformist, writer, trailblazing lawyer, saint, and more—her life, her work, and her words have many things to teach us.

“I think we are finally ready for some of the deep and important observations and theory that Pauli forwarded, and sometimes created and gave names to,” said Barbara Lau, director of the Pauli Murray Project in Durham, North Carolina, an organization that promotes Murray’s vision and legacy.

Lau is working to open the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice, located in Murray’s childhood home in Durham, which has just received historic landmark designation and a grant from National Park Service.

"I will resist every attempt to categorize me."

“I will resist every attempt to categorize me,” Murray wrote in the same article in 1945, “to place me in some caste, or to assign me to some segregated pigeonhole.” It is obvious that she lived according to these words as soon as you read about her. And, Lau says, learning more about Murray may lead you to join “the church of Pauli Murray,” made up of those inspired by her lifelong struggle for justice.

Born in 1910 in Baltimore, Murray moved to Durham in 1914 to live with her aunt. After leaving Durham to live in New York City, she attended Hunter College. She attempted to attend the University of North Carolina for her graduate degree knowing that it was a segregated school, but was not admitted. This was one of the many times she resisted segregation and discrimination. In 1940, she was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a bus to a white passenger in an act of nonviolent resistance, 15 years before Rosa Parks did so in Alabama. She continued to stage lunch counter sit-ins and other actions while at Howard Law School.

In 1944, Murray graduated from Howard, first in her class and the only female. It was around this time she developed the idea of “Jane Crow,” describing how the discrimination she experienced as an African American intersected with the discrimination she received because she was a woman. Her writings laid the groundwork for the idea of intersectionality. Ruth Bader Ginsberg cited her work in 1971 when she wrote the plaintiff’s brief for the Supreme Court, Reed vs. Reed, the first time the Equal Protection Clause was applied to women.

She had an important legal career, despite being denied opportunities because of her gender, race, and political affiliations (her friends included Eleanor Roosevelt and Langston Hughes). The book she wrote on commission from the Methodist Church about segregation laws, called State’s Laws on race and Color, was called “the Bible” for the Brown vs. Board of Education Supreme Court case by Thurgood Marshall.

Throughout all this, she grappled with her sexuality and gender. Today she might call herself transgender, describing herself at various times Paul, Pete, and Dude and seeking hormone therapy for many years to no avail.

“She invites us to ask ourselves, ‘What makes us whole?’” said Lau. “By describing her own experience and by trusting that her experience has value, [she invites us to] to trust that our experience is valid, even if it doesn’t fit in.”

This lesson still speaks today to the marginalized, especially those who are transgender. Black transgender people today face very high levels of discrimination, violence, suicide, poverty, unemployment, and homelessness.

"All the strands of my life had come together."

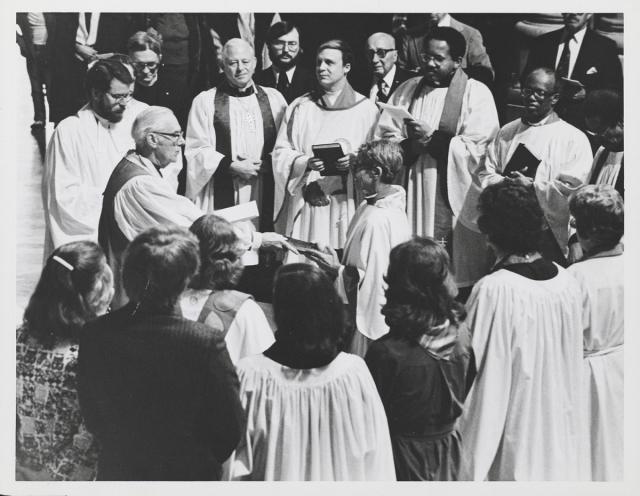

Not long after her longtime friend, and possibly her partner, died, Murray decided to enter The General Theological seminary in 1973. This was before the Episcopal Church allowed women to be ordained. General Convention approved ordination in 1976, just months before Murray was ordained to the priesthood. Her first Eucharist was celebrated in The Chapel of the Cross, in Chapel Hill, where her grandmother, the daughter of a slave and a slave owner, was baptized.

She wrote in her autobiography, “All the strands of my life had come together. Descendant of slave and of slave owner, I had already been called poet, lawyer, teacher, and friend. Now I was empowered to minister the sacrament of One in whom there is no north or south, no black or white, no male or female – only the spirit of love and reconciliation drawing us all toward the goal of human wholeness.”

Pauli Murray's ordination.

She served at parishes in Baltimore and in Washington, D.C. in the following years. Murray died in 1985 and she was added to the book commemorating Episcopal Saints and Holy Days, Holy Women, Holy Men, in 2012.

Murray is celebrated by the Episcopal Church on July 1. Every year around that time since 2013, St. Titus Episcopal Church in Durham, the church she attended as a child, has a commemorative service in her honor, using a litany written especially for her.

“We are using the story to continue her work, using that as the door into the bigger story,” said Lau. “What are we doing now and how are we learning from her? We are using the lessons of the past to address the issues we’re dealing with right now.”

It is not hard to see that the work of Pauli Murray’s life is far from complete, but her story provides inspiration to continue.

Trinity Church Wall Street is partnering with the Pauli Murray Project next year to help tell her story and inspire others in the struggle for justice. The project’s exhibit, “Imp, Crusader, Dude, Priest,” about Pauli Murray’s life and legacy will be on display at St. Paul’s Chapel, February 17 – March 21, 2018. A special community dialogue will be held the afternoon of March 11, 2018 on what Murray’s justice work teaches us about the pressing issues of our time and their historical roots. To Buy the Sun, a play that explores her life and legacy will be performed at St. Paul’s Chapel on April 5-7, 2018. For more information, email action@trinitywallstreet.org.

Sources:

Meet the most important legal scholar you’ve likely never heard of.

The Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray and the Episcopal Church

Anna Pauline (Pauli) Murray, Yale 1965 J.S.D., 1979 Hon. D.Div.